…or one year from life of a web/app developer, seeing broken HTTPS in the wild

All the things written below actually happened to my team, other teams at my company, or our external partners!

Who is this post for: web & app developers, devops, sysadmins; particularly if you’re working in a big company and roll out HTTPS on your own

Technical difficulty: low / intermediate (you know what is HTTPS, a CA, a certificate)

TL;DR: if you have only 2 minutes now, go to SSL Labs and check your domain. If you see anything in red or orange, compare your results with major websites like Google, GitHub, Microsoft, Guardian etc. If the given problem is not present on any major site, but only on yours, it probably means you need to fix it NOW.

Introductory self-Q&A

“I’m a just a developer and HTTPS is a devops things, do I really need to read all of that?”

If you’re a dev in a company migrating to HTTPS soon, or your newly created project will be using HTTPS, this post is for you. Even if your website is already in production, you may learn a thing or two.

Your devops will put things in place, and stuff will mostly work, but they might not know all the arcane details of all web browsers, and all requirements for your product, and then it will be you who will have to debug stuff. So at least glance over the headlines and TL;DRs to get yourself familiar with common issues.

“We have a staging environment, we’ll catch everything before long deploying to prod!”

Only as long as 1) your staging env has exactly the same HTTPS cert and config as production (in big companies, it might not be the case, due to domain name differences and internal policies), and 2) you test all possible browsers and operating systems (but it may still not be enough!)

“Is it really that hard?”

If you don’t want to break things for the end-users, it takes time. Have a look for example at this blog from The Guardian.

I will try not to repeat too many obvious things in this guide. I assume you already know basic stuff about HTTPS from different sources. Instead I will point some things that might be easily overlooked, or not noticed at all if you’re (un)lucky - until you have an urgent issue in production..

Forgetting about certificate expiration

TL;DR: don’t rely only on a once-a-year email reminder

I temporarily break my promise and start from trivial yet costly mistake, similar to forgetting to renew a domain, but it happens nonetheless. At least every few weeks I stumble upon a high profile page with expired cert, or a near-miss.

Obviously you should have a well-defined process, with email reminder and someone responsible for taking the action, but…

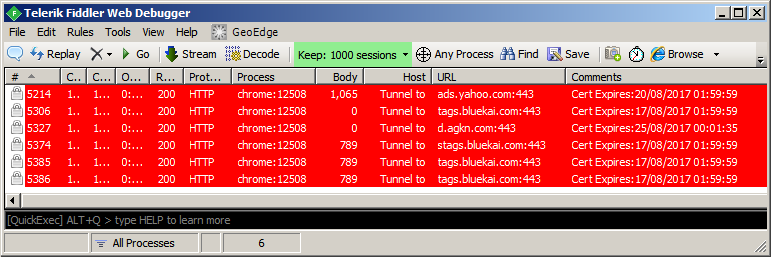

Apart from that, if you use Fiddler regularly, you can use a few lines of FiddlerScript to highlight HTTPS sessions that are using soon-expiring certs (thanks to Eric Lawrence for publishing it), so that the expiration catches your attention before it’s too late. You may want to customize it to only highlight sessions touching particular domain names of your interest:

if (e.Session.hostname.EndsWith("mydomain.net") ||

e.Session.hostname.EndsWith("mydomain.com")) {

e.Session["ui-backcolor"] = "red";

e.Session["ui-color"] = "white";

}

Don’t wait to renew the certificate on the last possible day (in particular when it expires on Sunday!) to avoid putting unnecessary stress on your team.

Missing intermediate certificates

TL;DR: run SSL Labs check on your domain and if you see “Extra download” in certification path, go now and fix it and come back when done!

First, quick primer on how CA (Certificate Authority) system works. Let’s use GitHub as an example.

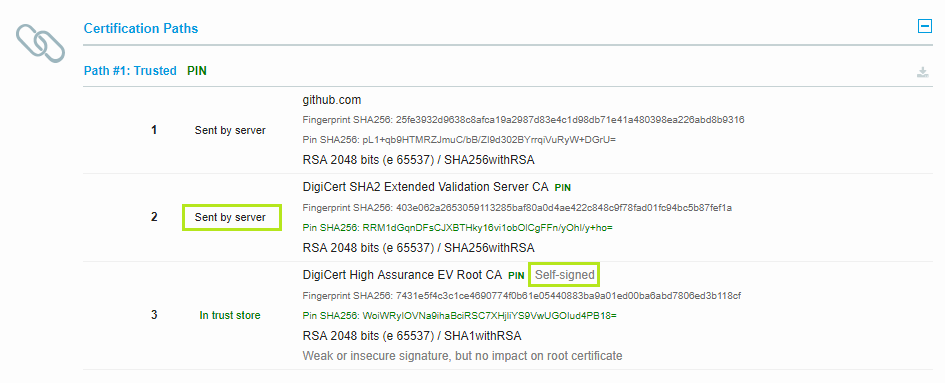

In the image below you see a certificate chain for github.com. There are 3 certs in play:

- Server cert (leaf): This is GitHub’s public cert that they use to secure the TLS session with the user’s browser.

- Intermediate cert of DigiCert, a Certificate Authority which signed (i.e. verified the authenticity) of the cert from GitHub (cert #1).

- Root cert (high-trust cert) of DigiCert, which signed (i.e. verified the authencity) of the other cert from DigiCert (cert #2). This cert, like all the root certs, is self-signed by the issuer; all the root certs are self-signed by definition.

Web browsers and operating systems typically ship with dozens and dozens of root certs embedded in their CA stores. When a server administrator wants to obtain a new certificate, the Certificate Authority, for operational reasons, will not sign it with a root cert directly, but instead it will do it with an intermediate cert. Anything in the chain between leaf cert (yourdomain.com) and the root cert is an intermediate cert. In a typical situation, there are 1 or 2 intermediate certs.

To verify the website’s cert, the browser needs to have a full chain of certification, to verify trust of each link of the chain. The leaf cert is always sent by the server, the root certs are available in the browser, but where does the browser get the intermediate certificates from? There are two options:

- either server sends all the intermediate certs,

- or the browser needs to get them from somewhere.

The screenshot above shows GitHub properly sending the intermediate cert. But what happens in the other case? It’s implementation-specific, depends on the browser and platform:

- if the browser happens to have an intermediate cert cached locally, because some other website that the user has visited served it, it will be reused;

- if the intermediate cert is not cached, some browsers will fetch it, but some won’t; in particular, Android WebView and all versions of Firefox do not fetch any missing certs!

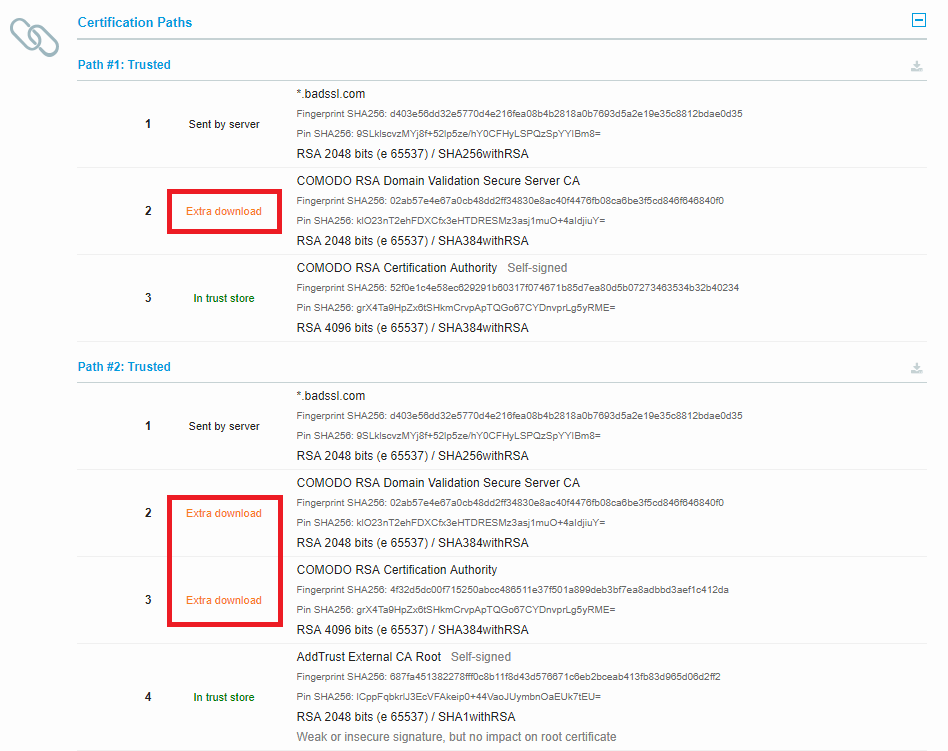

See an example of a misconfigured server below:

This servers’s cert can be verified via two certification paths (because the intermediary cert has been cross-signed by two different certs), but unfortunately none of paths can be reliably resolved by the browser without an extra download.

If you see “extra download” in SSL Labs, go now and fix it! Your page might be randomly not working for many of your users (but it might be sporadic enough that you don’t get any reports).

See also:

TLS 1.2 and old Androids

TL;DR: make sure you don’t lose dozens of thousands of users before you roll out TLS 1.2

HTTPS deployment is a fine balance between security and backward compatibility. The gold standard in 2017 is TLS 1.2, but it’s not supported by old operating systems and browsers (Internet Explorer on Windows XP, and very old Androids).

Supporting outdated browsers means supporting insecure crypto and lowering security for everyone else. While most of the Android developers have stopped supporting pre-KitKat devices long time ago, there’s still a significant market share of KitKat (Android 4.4). According to Android dashboard, as of July 2017, 17% of Android users still use KitKat. However, you should check the stats in Play Store console for the active users of your own app, and the stats there might be way different (as the variation between the countries is big).

The interesting thing about KitKat is that while it has the capability to support TLS 1.2, it’s by default switched off, and while some vendors do support it, many do not. (There are even reports of Samsung devices with Android 5.0 not supporting TLS 1.2, which in theory should not happen).

Due to PCI-DSS compliance, you might be forced to migrate your server to TLS 1.2, but you should double check your user base statistics before, to avoid recklessly cutting out a big portion of the market from your services.

The platform team in my company was very keen in late 2016 on migrating to TLS 1.2 (and removing support for TLS 1.1 and 1.0), but after some discussions we’ve decided to postpone it. We have reevaluated this summer, and we are finally planning to drop KitKat support and roll out TLS 1.2 in the coming weeks (end of 2017).

Using HSTS too aggressively

TL;DR: only roll out HSTS when everything else’s been checked and working well. Serve small max-age initially and increase as you gain confidence - or prepare to serve max-age=0 in case of problems.

HSTS is a very useful security header which tells the browser to “remember” to always load all URLs from a given domain over HTTPS, even if HTTP URLs are encountered, for a given period of time described by max-age field in the header value. In other words, it prevents you from visiting unsecured HTTP pages.

Usually this is good, but obviously not when HTTPS version is not working properly, and the user really wants to see the HTTP version.

Story time: We have an on-site JIRA instance in my company; put in place several years ago over HTTP, but work began lately on serving JIRA and everything else over HTTPS.

At some point, the implementation team enabled an http->https redirect and an HSTS header. For some reason though, it turned out some parts of the page were not working over https (not that obvious to diagnose for the end user), so the force-https config was disabled, and the recommendation from JIRA support team was to use http URLs.

But, with HSTS it is not that easy: if you ever visited https version before, when visiting http URL later, you were redirected back to https page (the whole point of HSTS after all!), and clearing standard browsing data didn’t help.

There are two solutions if your users get trapped by that problem:

- You could serve

max-age=0value for HSTS header which tells the browser to discard all HSTS data it has for the serving domain (but this is taken into account by the browser only when served over HTTPS - as any other HSTS header value). - Users may clear HSTS cache of the browser. Not very easy to do, and not user friendly; typically hidden in browser internals, for example:

chrome://net-internals/#hstsin Chrome.

Obviously, the best solution is to be cautious and only implement HSTS when everything else was verified; also, put a small max-age (a few hours, a few days) first, and gradually increase when no problems are found.

Read more:

Forgetting about www/nowww when deploying HTTPS, CDN, or security proxy

TL;DR: do not forget about nowww. Make sure it works over http and redirects to https.

Typically, your website has a canonical URL of www.example.com or example.com, so you have 2 entry points. Most likely you serve a redirect from one to the other, to avoid duplicated content.

However with HTTPS in the game, each of the two is accessible either via http or https, so you have 4 entry points total.

If you forget about your nowww domain, you might end up in the following situation:

- User types “example.com” in URL bar

- The server responds with a redirect to “https://example.com“

- Your HTTPS cert is not valid for nowww domain -> scary warning, user runs away.

Another thing that could happen is that your traffic to nowww domain won’t be resolved at all and user will think that your page is down.

The problem is so prevalent that modern browsers have some built-in magic to probe www domain in case of nowww not working, but as with any error recovery mechanism, it’s better to not rely on it.

Actions:

1) Make sure to choose one canonical entry point (say, https://www.example.com) and put redirects in place in your webserver’s config for the 3 remaining ones:

- http://www.example.com -> https://www.example.com

- http://example.com -> https://www.example.com

- https://example.com -> https://www.example.com

(You might want to write a simple bot that checks all of this each night and alerts you if a redirection stops working. Subsequent configuration changes, perhaps done by external teams – not unheard of in corporate environments – might break that redirection without anyone noticing.)

2) Since example.com and www.example.com are different origins, a regular TLS cert with just one explicit domain name won’t work for both. You need a cert with SAN (Subject Alternative Name) matching both, for example: *.example.com example.com or www.example.com example.com

3) SEO tip: Generate <link rel="canonical" href="https://..."> in the <head> of your HTML responses to make deduplication work easier for web crawlers.

See also the following support entries from Google Webmasters:

Part 2

If you made it that far, you should check part 2, where I discuss: sending extraneous certificates; randomly sending wrong certificates; sending a certificate signed by a not widely-accepted root cert; and provide some links to helpful tools and external resources.